They call themselves the Library Ninjas, and they come to the Busia Community Library to watch movies, eat bananas, and drink clean water. The library opens at nine in the morning, and on Thursdays each week a crowd of kids is already waiting. These kids live on the streets and make their money begging and running small errands at the border between Kenya and Uganda, which runs through Busia Town. The movies don't start until 11, but the kids show up early each week, even before the librarians.

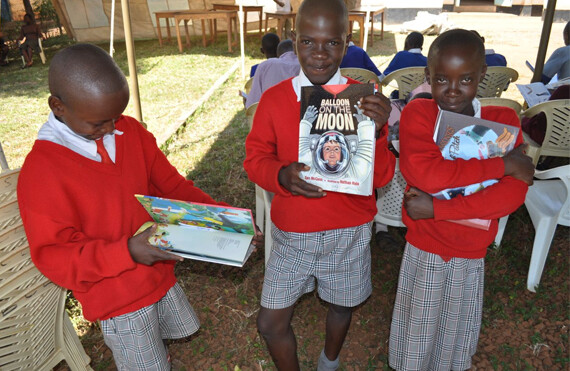

For the Library Ninjas, the Busia Community Library (BCL) is the only safe public space they have. Some of the Ninjas attend school, despite living on the street, but for most of them the library is also the only place where they can access books. While waiting for the movie to begin, the kids read and use computers.

The Ninjas are not the only group to have found sanctuary in the library. Currently located in two small rooms in a government office building, the library hosts an average of 30 visitors on a typical day, from a broad spectrum of the community. The patrons come for a variety of reasons—from researching farming practices to checking email to accessing materials regarding government services or laws. One government official comes to the library every day during lunch to read books about human biology, out of personal interest.

During school vacations, the number of visitors leaps dramatically, sometimes exceeding capacity. On those days, library users check out their books and sit in the parking lot.

The Busia library was opened in 2006 by Family Support Services, a community-based organization. At the time, I was doing research in Busia on economics and health. I, too, was looking for books when I discovered the library, only to find it wasn't well stocked. I began helping them to grow the collection.

I moved away from Busia to work on international development policy, and the more I became exposed to real-world challenges at the global level, the more I became convinced that libraries can be a critical tool to support a number of development goals. In 2009, I co-founded Maria's Libraries to offer more systematic support to the Busia Community Library, and to support a network of libraries across Kenya.

Why Libraries?

Libraries are of course not a new idea. But the two principle elements of libraries—their functions as public spaces and as access points for information resources and technology—make them the perfect places to reinvent community development. Building a library network where before there was none also affords the opportunity to reinvent what libraries mean in the digital age. At Maria's Libraries, we use the public space aspect of libraries to engage community members in developing new information services that are designed to their needs.

People who grow up with libraries intuitively understand the role they play in people's lives. For some, libraries offer a gateway into other worlds through books or the Internet. I recently spoke with someone from the Lyuben Karavelov Regional Library in Bulgaria, which has become a center of support for the unemployed seeking long-term employment. In Kenya, libraries are some of the only places where one can find reading material for the blind. There is a library in Portland, Maine that has video drop-in hours for people in rural areas who don't have access to lawyers. In New York, there is a library with a program for fathers in prison to read stories to their sons.

People across the world with access to libraries have deeply personal relationships with them.

On an institutional level, defining libraries may seem fairly straightforward: They are places with books and other resources available for public use. That's a great start, but it is only a start. Our research and work at Maria's Libraries has led us to redefine how libraries are conceptualized based on critical issues in international development.

Information needs are cross-cutting

Libraries can support the achievement of multiple development goals. For example, the Millennium Development Goals call on the global community to organize around issues related to poverty, maternal and child health, education, HIV/AIDS and malaria, environmental sustainability, and more. Thousands of entities globally have organized to tackle these challenges.

Although current thinking in development points to the virtuous circle that is created when challenges are addressed together (an "ecosystems approach"), these issues are so diverse and complex that it is difficult for one organization to comprehensively address even one of them, let alone all of them.

However, there is one thing that is required across all of the MDGs: They require citizens to have better information. What is more, they require interaction around information so that citizens can act upon it. Libraries, as public spaces that centralize access to information resources, can play a clear role in addressing this gap across development challenges.

Library users define their own needs

Enabling participatory development or community-led approaches has been a much-discussed alternative to top-down development institutions for decades. Libraries can help! As public spaces, they allow individuals or groups to access resources around self-defined needs. International organizations or governments can provide services through libraries; but libraries can play a role in enhancing existing or nascent civil society initiatives simply by their presence. If libraries are developed such that they are responsive to the information needs of the users, they can allow for truly community-led development initiatives to emerge.

What is more, if library services are demand-led, they can also serve as a hub for other types of services that might not be what people first think of when they think of library. For example, libraries could have a "tool shed," where farmers could borrow agricultural tools. Or they could act as a place to centralize access to electricity, where people can charge their mobile phones or other devices. The possibilities and needs will vary depending on the location.

CREDIT: © Maria's Libraries.

As an example of how libraries can foster demand-led programming, let's return to the Library Ninjas. When Maria's Libraries started what we were calling our "street kid program," our only goal was to establish the library as a space where street kids felt comfortable. Once we did the heavy lifting, our idea was to ask the kids what they wanted from the library, and respond to what they told us. Our outreach coordinator spent a couple of hours visiting the kids where they hang out at the border, telling them to come to the libraries to watch movies. The first week, about five kids came.

Without any additional outreach, that number doubled the second week, and continued to increase until it held steady at around 20 kids per week. That was beyond what we had anticipated, and we have found ourselves scrambling to keep up with their enthusiasm. Our first steps were to do two things: 1. We looked for any other local services for street kids that we could provide information about or access to through the library; and 2. We began to do some ideation exercises with the kids to design their own solutions to their own challenges.

What we found was that the existing services do not meet the needs of this population. For example, the Child Protection Officer focuses on sending the boys to juvenile detention centers, or back to the home environments they have fled in the first place. When we went through the types of challenges the boys face, they cited the protection programs as threats to their security, even though the programs were intended to support them.

During this process, they asked that we stop referring to them as street kids, and through a dedicated brainstorming session a new moniker was settled on: the Library Ninjas.

Currently, the Ninjas are working towards two projects, with another project in the works. First, they would like agri-business training, and we are currently aligning the appropriate partners and funders to form a Library Ninjas cooperative. They will be taught poultry farming, as well as business and financial management skills. Second, the Ninjas would like to be respected as contributors to society. We are currently working with the library in nearby Kisumu, Kenya to create mechanisms whereby the Ninjas' voices can be heard.

The Ninjas have also requested a shelter or group home with rules that ensure both flexibility and security. We are still in the process of finding organizations that may be able to help in the realization of this goal. Once these projects are underway, the library will not be involved, but will have brought together the appropriate partners to undertake the programs. The library will continue to actively seek to centralize access to opportunities for the Ninjas at the library. We will also continue to show movies, and provide clean water and bananas.

Libraries are existing, multi-use infrastructure

One library can do a lot to promote community development. A network of libraries can do a lot more. In Kenya, there are 54 libraries in the national library service (KNLS). There are many more libraries outside of the KNLS system, but there is no comprehensive list. Maria's Libraries works with a pilot network of five libraries, located in diverse regions of Kenya, to understand how best to encourage connections between sites.

One way to think of a network of libraries is like a network of labs, where innovative ideas can be tested out in different contexts, and successful projects can scale naturally throughout the library system. With a properly functioning network, this can allow ideas that arise from one community to spread to others.

In the work of Maria's Libraries, we have seen this happen through guidance documents aimed at supporting librarians wishing to implement our programs at other sites. These documents encourage librarians to adapt the program to their own community. We have thus seen our programs implemented by other groups in Kenya—we have also seen them being implemented in libraries in other countries. It is interesting that libraries have had different goals in implementing the same program.

CREDIT: © Maria's Libraries.

For example, the Mama Mtoto Storytime Project, in which young mothers are taught to read storybooks to their preschool-age children, was used by two organizations outside our network. The first was a group in Kenya interested in early childhood education. When they implemented the project, they focused on multi-language books that could ease children into the learning environment they would experience at school.

The other was an organization in Rwanda providing medications to young mothers with HIV. The organization was having trouble getting the mothers to adhere to the treatment schedule, so they were exploring the Mama Mtoto program as a way for the mothers to feel increased value in their lives.

A library network is a national resource

Another way to think of the network is as a national resource. For development practitioners seeking to implement projects in new sites, libraries are spaces where programs can be implemented, whether in one location, one region, or nationwide. With or without a full-fledged program, libraries are great places for nonprofits, governments, or international institutions to provide information resources.

For example, Kenya recently adopted a new constitution. In our surveys to assess community needs, we found that while people expressed excitement about the constitution, many also expressed uncertainty about what it actually means for them.

Several organizations in Kenya work to address this knowledge gap. One organization produces pamphlets and other materials aimed at outlining the new constitutional rights in an accessible way. Another organization holds an annual Legal National Awareness Day. At Maria's Libraries, we are currently assessing how libraries can support this.

As existing infrastructure, libraries are physical locations where a National Awareness Day can be celebrated. In addition, while it is not the role of the library to develop materials related to understanding the new constitution, libraries could be a critical access point for materials which are developed by other groups.

Working to strengthen library networks thus strengthens civic engagement, and could allow the emergence and spread of community-led initiatives, and facilitate access to national or international programs.

Conclusion: Looking ahead

Maria's Libraries is currently working with Kenya National Library Services and the Busia County Government to build a new library in Busia. This library will be modern and innovative by global standards, and will be designed to enhance the ability of the library to foster community-led development. The library will have the books and technology traditionally associated with libraries. It will also have the only public auditorium in Busia County, a coworking space, and a citizen science center that functions both as a resource for schools and a DIY "makerspace."

We hope this library will influence other library initiatives around Kenya. Indeed, although construction on the new library has not yet begun, we are already seeing other communities picking up the model of library services from Busia. Nearby Bungoma County has been speaking with the Busia Library Committee to learn more about their experience, and is currently in the process of securing land for a new library there.

As we go, we're learning about the best way to strengthen the network of our pilot group of libraries. Once we have the model down, we'll start expanding the network to other libraries. We'll know that we're successful when the libraries start collaboratively designing programs without our involvement.

By learning from our experiences and the experiences of other organizations, Maria's Libraries seeks to reinvent what libraries can mean in the communities where we work. In doing so, our goal is to strengthen the ability of communities to learn, seek, and grow around self-defined challenges.

CREDIT: © Maria's Libraries.