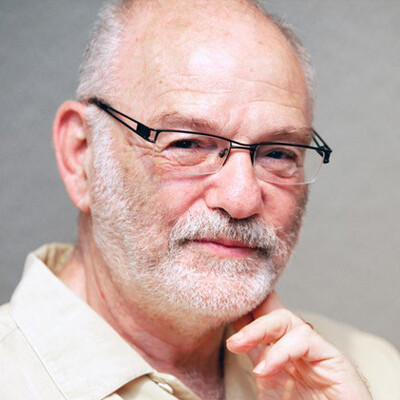

在本期 "人工智能与平等 "播客中,高级研究员温德尔-瓦拉赫(Wendell Wallach)与香农-瓦洛尔(Shannon Vallor)教授坐在一起,讨论如何重新审视伦理学,使其有能力应对人工智能、新兴技术和信息时代的新权力动态。

WENDELL WALLACH: It gives me great pleasure to welcome my longtime colleague Shannon Vallor to this Artificial Intelligence & Equality podcast. Shannon and I have both expressed concerns that ethics and ethical philosophy is inadequate for addressing the issues posed by artificial intelligence (AI) and other emerging technologies, so I have been looking forward to our having a conversation about why that is the case and ideas for reenvisioning ethics and empowering it for the information age.

Before we get to that conversation, let me introduce Shannon to our listeners, provide a very cursory overview of how ethical theories are understood within academic circles, and provide Shannon with the opportunity to introduce you to the research and insights for which she is best known.

Again, before turning to Shannon, let me make sure that listeners have at least a cursory understanding of the field of ethics. Ethical theories are often said to all fall into two big tents, and one of those tents—the determination of what is right, good, or just—derives from following the rules or doing your duty. Often these rules are captured in high-level principles, that the rules can be the Ten Commandments or the four principles of biomedical ethics. In India they might be Yama and Niyama. Each culture has its own set of rules. Even Asimov's "Three Laws of Robotics" do count as rules meant to direct the behavior of robots.

All of these theories are said to be deontological, a term going back to the Greeks, referring to duties, and it is basically saying that rules and duties define ethics—but of course there are outstanding questions about whose rules, what to do when rules conflict, and how you deal with situations when people prioritize the rules very differently.

At the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries, Jeremy Bentham, a British philosopher, came up with a totally different approach to ethics, which is sometimes called utilitarianism or consequentialism. Basically, Bentham argued that you don't determine what is right, good, and just by following the rules; you do so by determining or considering the consequences of various courses of action and following that course that leads to the greatest good for the greatest number.

Bentham's utilitarianism or consequentialism was later developed more fully by John Stuart Mill, but it also has limitations— for example, what do you do if the greatest good for the greatest number might entail serious harms to a minority?

Though these two tents have been what most ethical theories fall within, there has always been a third tent in determining what is right, good, and just, and that is often referred to as virtue ethics. In the West it is often identified with Aristotle and his Nicomachean Ethics, but in the East it is identified with the thought and work of Buddha and Confucius. It basically argues that the core thing in ethics is the development of character through practice and habit and what is right, good, and just is determined by what a virtuous person, a moral exemplar, would do.

Within virtue ethics there are also debates over what are the core virtues or who deserves to be considered an exemplar, but virtue ethics for most, or at least the latter half, of the 20th century was largely captured by those of a conservative political persuasion. Yet, in recent years it has been taken up by many philosophers of technology, a small cadre at least of which Shannon is often seen as the leader.

Shannon is a philosopher of technology. She is the Baillie Gifford Chair in the Ethics of Data and Artificial Intelligence at the University of Edinburgh Futures Institute, where she directs the new Centre for Technomoral Futures. She is perhaps best known for her book Technology and the Virtues: A Philosophical Guide to a Future Worth Wanting to which I will be returning in a minute.

Before coming to the University of Edinburgh she had been a professor at Santa Clara University in Santa Clara, California, since 2003. During her fascinating career she served as president of The Society for Philosophy and Technology and was the winner in 2015 of the World Technology Award in Ethics.

But Shannon is not an armchair philosopher. As Google is being challenged over its ethics, it approached her to serve as a consulting AI ethicist for its cloud AI initiative. Shannon is also the editor for the forthcoming Oxford Handbook of Philosophy and Technology.

Let me first turn to Shannon and the book for which she is most known, Technology and the Virtues: A Philosophical Guide to a Future Worth Wanting, and ask her to give you at least a brief overview of what that book is about.

SHANNON VALLOR: Thanks, Wendell. Thanks for that kind introduction and thanks for inviting me to be a part of this conversation.

When I wrote the book, I was in a place where all of the literature that I was reading—about the ethics of emerging technologies from social robots, to artificial intelligence, to biotechnologies designed to modify the human genome—around the ethical implications of these emerging technologies was pretty much drawing only upon these deontological frameworks or rule-based approaches or, alternatively, applying these utilitarian frameworks that you have described.

It seemed to me quite obvious that this ignored, as you say, a whole swath of ethical territory that actually is older than the utilitarian approach and certainly not any less influential in the history of ethical thought than rule-based approaches, and that is that "third tent" that you mentioned, the virtue ethical approach, which in the West, as you say, we tend to regard as growing out of the work of Aristotle and later thinkers, but there are, as I described in my book, also virtue ethical traditions that can be found elsewhere in the world, from classical Confucianism, which is broadly conceived as operating on a virtue-driven or character-driven model that emphasizes not the rules that one follows but the kind of person that one becomes and the specific habits and practices that make you into that sort of person.

What is common across virtue traditions—whether we look at the aspects of Buddhism that are well described as appealing to virtues or whether we look at the Confucian tradition, the Aristotelian tradition, or more recent attempts to provide more contemporary versions of accounts of virtue—all of these share a common idea, which is that we are not born virtuous, that we become virtuous, if we do, only through our own efforts of moral self-cultivation, and that involves a number of practices and habits that are part of our daily existence.

Aristotle said essentially that we are what we repeatedly do, so we often hear people in society say something like "That wasn't my intent" or "That's not who I am" after being called out for a pattern of harmful behavior. What's powerful about the virtue ethical lens is it says: "If this is what you repeatedly do, this is who you are, and your self-conception or your excuses mean very little; what matters is the kind of person you have allowed yourself to become through the repetition of certain kinds of actions."

What is powerful to me, and what drove me to write this book, is the recognition of two things.

The first is how much technology reshapes the kind of people that we are precisely by reshaping the kinds of habits and practices that we engage in on a daily basis. The first inklings of thought that turned into this book emerged during the introduction of the first smartphones and the introduction of technologies for social media platforms like Facebook. My students were having their relationships, the way they talked to each other, met with each other, and communicated with one another radically transformed by these technologies, and I was seeing my own habits and practices transformed by them. If I compare the way I went about my day pre-Twitter and post-Twitter, there are some stark differences, and they have shaped my character for better and for worse.

I was recognizing that we were not talking about this. We were not talking about how technology actually shapes the ethical landscape. It is not simply that our ethics has to be applied to technology, we also have to think about how technology reshapes our ethics.

The second thing that I had to take account of in this book is the way that our technologies have global reach, scale, and impact, and that relying on ethical frameworks developed only in the Western European or Anglophone philosophical traditions was obviously not going to be apt or responsive to a diverse range of global considerations and needs that people and communities have from and in light of our new technologies. I thought: What do we do about that? What do we do about the fact that we have technologies acting upon us at global scale that, if they need to be governed or steered in particular directions, that is going to require collective decision-making at a global scale, and yet none of our ethical frameworks are global? And they really can't be. There is no one ethical framework that can be meaningful, I think, to all humans in all places and times.

But what I found in this book—and this is where I will wrap up my introduction to the book—was that, although there are no universal or global ethical theories, there is this under-layer of common ethical practices, of moral self-cultivation, that get pointed to by different cultures, developing accounts of virtue that are very different but that build upon the same practices of moral self-cultivation, practices like relational understanding, reflective self-examination, moral attention, and prudential judgment, and I started looking at how these practices can help us develop a truly 21st-century ethic for dealing with emerging technologies by building on these common human practices of making ourselves into the people that we want to be and need to be for one another.

I talk in the book about how that might be applied to different technologies—from military robotics, to robots caring for us in our homes, to technologies meant to change human nature, to social media platforms—so I have since then been thinking about what else needs to be done to make an ethical framework that is truly robust, inclusive, and responsive to the new and uncertain reality that technologies are shaping.

WENDELL WALLACH: As I understand it, you are working on a follow-up book that you at least call presently The AI Mirror: Rebuilding Humanity in an Age of Machine Thinking. How about sharing a few of the insights from that with our audience?

SHANNON VALLOR: Yes, happy to talk about that.

One of the things that I think is really interesting about AI is that it distracts us actually from paying attention to what is happening to our own thinking processes. When I talk in that title about "machine thinking," it's sort of ambiguous. It is meant to point to this story we're being told, that we now have machines that can "think like we do."

That story is false, and every serious AI researcher knows that it's false, that the AI systems that we have today don't think like humans do and they are not intelligent in the ways that humans are, they are simply very clever tools that use powerful mathematical techniques and large mountains of data to perform tasks that previously required human intelligence. So what we have are not intelligent machines, but substitutes that are practically useful in many contexts for human intelligence.

So when I refer to "machine thinking," I am not actually talking about AI. I'm talking about ourselves at that point in the title, because what we are seeing—and this predates AI and it is something that has been commented upon by philosophers, sociologists, and computer scientists themselves for decades, going back to the postwar period—an emergence and a strengthening of a regime of mechanization of human thought and applying bureaucratic and technical pressures upon human beings in order to reshape their thought patterns in ways that can be better accommodated by machines.

Instead of using the machines to liberate and enlarge our own lives, we are increasingly being asked to twist, to transform, and to constrain ourselves in order to strengthen the reach and power of the machines that we increasingly use to deliver our public services, to make the large-scale decisions that are needed in the financial realm, in health care, or in transportation. We are building a society where the control surfaces are increasingly automated systems and then we are asking humans to restrict their thinking patterns and to reshape their thinking patterns in ways that are amenable to this system. So what I wanted to do was to really reclaim some of the literature that described that process in the 20th century—from folks like Jacques Ellul, for example, or Herbert Marcuse—and then really talk about how this is happening to us today in the era of artificial intelligence and what we can do about it.

It is not a book that intends to blame AI for this. This is a phenomenon, as I have said, that long predates the commercial development of artificial intelligence, but I think that AI is amplifying this process and speeding it up and I think that we need to rethink what AI can be and what it can do for us because I think those possibilities of using technology to liberate and enlarge our lives are still available to us if we want to reclaim it, and that's what that part of the title is about, reclaiming our humanity.

WENDELL WALLACH: That's what I love about your work, that it is so human-centric in light of all these forces that are being put upon us both by the technologies but also around these narratives that are suggesting that we are not only flawed but that the technologies are going to be superior to us and that we need to be conforming our behavior to the technologies rather than asking that the technologies become more a reflection of who we are, what we need, and how best again we can put the cultivation of character back at the center of human life.

It seems to me that a lot of that has been lost through the weakening of religious traditions that so much of character development was identified with and notions, many being perpetuated within academia, that somehow all of ethical understanding or all of ethical judgment can be either reduced to characteristics that we inherited from our evolutionary ancestry or reasoning processes that can be performed better by machines than they can by people. I just find it very exciting that you are doing so much to focus attention on character development.

As you know, that has been important to me throughout my life. I have meditated for 50 years and think that self-understanding and the kind of natural character development that may emerge out of that is a lot more important than your ability to hone a rational argument, which is often just a rationalization for what you're doing.

SHANNON VALLOR: I was just going to say—and it's funny that you mentioned religion and its place in moral guidance and development—this too was actually predicted by the philosophers of technology of the mid-20th century who saw this creeping intrusion of something we could call the "technological sublime," the kind of terrifying but also attractive force and mystery of technosocial power and technoscientific power, that as this grew in the 20th century, it came to intrude upon the place of religion in a number of ways. Jacques Ellul talks about "the sacred" and how the rule of technological efficiency itself becomes the focal point of our perceptions of the sacred and it becomes the thing that we will sacrifice all else to protect, honor, and preserve.

It's funny when you look at online culture today and you look at who people speak of in reverent tones, it's not religious leaders primarily and it's not your average political leader—most of them are treated with cynicism and scorn—it's often these figures in tech. They go through cycles of being revered and being disdained, but there is this searching for the divine and the prophets of the new world are being sought in places like Silicon Valley, which is a very perverse place actually to look for the divine in a lot of ways.

And yet, there is this gap that has been created, I think, between power and goodness, which have always been in tension, but I think the divorce between power and goodness is as stark today as it has ever been. That's partly because technology is the domain increasingly where power is concentrated, but we have long treated technology as if it's neutral, as if it's not a domain where values apply, and what philosophers of technology of course spend much of our time doing is explaining why that is false, why technology has always been human, why it has always been embedded with ethical and political values, but as long as we don't see that, we won't be able to reunite this breach between the power that we have to change the world and transform it and the power that we have to do what is right to take care of one another and our world.

WENDELL WALLACH: What has fascinated me about this is the extent to which we can turn to past traditions and perhaps reformulate them and revitalize them for the present and the extent to which that might be inadequate.

I get very caught up in the question of: Well, how much is it just getting people thinking about virtues and character development again, and all these qualities that are going to be very hard, if not impossible, to imbue in our technologies and, therefore, there is a really important role for humans in both the present and the future development of these technologies? Or whether we need to be reformulating how we think of ethics more generally and perhaps bring in totally new elements that have not been given adequate expression so far?

How do you see that, particularly given that you have played such a prominent role in re-enlivening the attention that virtue ethics deserves?

SHANNON VALLOR: I think my interest is in understanding ethics as a form of creative response to the world and the challenges that it presents, so I don't think ethics is something fixed.

One of the things I wrote about in my first book was the fact that the ethics of past eras won't serve us today—even though I'm diving into those old texts in the book to reclaim these more fundamental practices—but the world that they describe is a good world, and the world that they have developed notions of virtue in order to protect and preserve is not a world that we can have in the 21st century. We are not able to support 8 billion people by going back to living like the ancient Greeks or 6th-century Confucians. This is not going to be the way that we provide for human flourishing and planetary flourishing in the 21st century.

So we need to free ourselves to be able to think about new ethical visions, but we also have to think about where our current ethical vision is failing us and confront that honestly. I think it's failing us—I will focus on three areas:

One is it's failing us because most of our ethical theories—particularly in the West, but even in traditions like Confucianism—have primarily treated ethics as a matter of individual character and individual decision-making, so we have an ethics for individual moral agents that is about individual responsibility, individual rationality, and individual virtue. That doesn't cut it in a world where our problems are not personal problems so much as existential problems that affect the entire planet that cut across national and cultural boundaries and that require radically different kinds of communities to come together and shape intelligent policy.

You have worked, for example, in the area of governance of the kinds of technologies that are being applied in military contexts, as have I, and we both know how challenging it is to form a kind of coherent ethical vision of the future of military technologies when you're dealing with people who have very different views of ethics, of human rights, and so forth.

We have to be able to recognize that an ethics that doesn't talk about collective decision-making, collective action, or collective deliberation is not going to serve us well. That's one. We have to think about what an ethics that works at that higher social level and that allows divergent minds and bodies to cooperate and develop policies that help them flourish together. That's an ethics that we don't have and that we desperately need.

The second thing that we need is an ethics actually that dispenses with some of the biases that have been inherited by worldviews that have primarily been developed by a small subset of the population—elite men, almost exclusively, who were in positions of privilege and power and used those to craft their theories of how people and society should be.

One of the costs of that, for example, is seeing something I have been really looking into deeply lately, which is the way that values like care and service to one another are devalorized in ethical traditions like Aristotle's, where he explicitly says that people who are skilled in crafts and arts should not be allowed to be citizens precisely because the crafts and arts are used to provide necessary services to others, and this is debasing or demeaning for Aristotle.

WENDELL WALLACH: This is truly a fascinating insight that you derive from Aristotle. You are the only person I have ever heard even point to that.

SHANNON VALLOR: It's really striking because it made me realize how much our ethics doesn't talk about things like care and service and didn't —until feminist ethical traditions in, for example, the 1970s and 1980s—begin to develop an independent approach to ethics known as "care ethics," that reclaimed these values.

But what would the world look like if those had been the dominant ethical values all along? What would our planet look like if an ethics of care have done for our world rather than an ethics of rationally consistent agency, utility maximization, or happiness maximization? We don't know, but I think we need to look to these kinds of alternative values, the values of restoration.

There is some interesting work being done on the notions of maintenance and restoration as core ethical values. We focus on creation, building, and innovation while we let our bridges and our roads crumble, and the things we have already built we don't care of, and we simply replace them, often with alternatives which won't last as long. We have laws that prevent people from repairing their own devices. There are a lot of interesting ethical movements to change that, so I think that's something that we need to look at.

WENDELL WALLACH: A lot of this seems to be a reflection of the Enlightenment ethical tradition that has dominated the development of modernity and now seems to be collapsing under its own success. I think people lose sight of the fact that that was a response to or a compensation for the fact that the religious, ecclesiastical, and Aristotelian scholasticism which dominated the world that that came out of was collective in ways where it stifled individual expression and it made the world very much about striving for an afterlife, as opposed to transforming the quality of the world that we were in.

Of course, what is so fascinating is how that has been perverted, as an aggrandizement of individualism and of individual freedoms in a way where there is almost no need to be concerned about the impact of your individual freedom on the community at large or on humanity at large. That is going to be difficult for us to get away from, and difficult particularly if we don't expect something more than success from those who are leading the tech revolution.

SHANNON VALLOR: Yes, that's right.

I also worry about the sort of backlash to that excess becoming a potentially destructive reactionary movement in itself. The anti-Enlightenment backlash has its own dangers, and so we need to be able to step back and ask: "What is it about the Enlightenment that we have good reasons to preserve and reclaim and honor in a better way, and what are those aspects of the Enlightenment that honestly we should have the courage to go beyond and set aside?"

I think we have right now a culture that reinforces notions of opposition and extremity, so people are either doubling down on the Enlightenment vision and pursuing it in increasingly reckless and destructive ways, or they are trying to get as far away as they can from that vision without always being guided by something that is in itself just and sustainable.

That's where I think coming back to these other values might help us—values like care, values like love. What would it mean to have a world of technologies where care, love, service, and restoration were the things that designers had in mind, as opposed to efficiency, optimization, speed, or scale, which are the values that drive technosocial innovation primarily today?

WENDELL WALLACH: The values that drive technosocial innovation aren't going away.

SHANNON VALLOR: Sure.

WENDELL WALLACH: So now we're trying to introduce values that are often identified with—I think you're correct, that feminism is really what brought those values to the fore largely in the 1960s and 1970s, but they were obviously getting expressed well before then.

There is this problem of how you integrate those values into the mechanisms of not only capitalist productivity and efficiency but also governance and international relations, and whether they can prevail or whether there is a kind of Realpolitik about why things are the way they are that has wedded us to a form of inevitable machinery that is going to lead to an arms conflict, an AI militarization, or to the onset of smarter-than-human machines, the inevitability of that, and the necessity for us to defer to them in decision making because ostensibly they're supposed to be more intelligent than us.

I see that there are kind of three different wings going on there: (1) the revivification of some older traditions that aren't getting their due; (2) there is this expression and building and empowerment of values that have always been around but haven't really been integrated into our social fabric effectively, so that becomes our care, humility, compassion, that whole inter-human framework or interpersonal framework or social framework that is so essential for us to cooperate with each other; but (3) there also seems to be a tremendous pressure to diffuse the techno narrative that is driving Silicon Valley and driving their belief in what the future is and should be and therefore we should all just get out of the way.

In fact, that is perhaps one of the areas in which you and I came together. Some of the first activity that Shannon and I did together was around a series of workshops that I and Stuart Russell co-chaired, which were among the first workshops that actually brought the leaders in the development of AI together with philosophers, ethicists, engineering ethics, and people who were looking at machine ethics, designing robotics or AI that was sensitive to ethical considerations and in fact have added to its choices and actions.

It was a kind of fascinating session, in that I thought that it was destabilizing the narrative, but then I only went on to witness how the narrative went on in spite of some very direct challenges, some of which you made so clearly to some of the leaders of AI.

I am not quite sure how we're going to get around that. They seem to have an unbelievable megaphone at the moment and a capacity to argue that: Since we really don't understand and only they understand the technologies they're developing, we're going to have to defer in the short run to them in terms of how these technologies get managed.

SHANNON VALLOR: Yes. I think we have a couple of things going on here.

One is the kind of naïve religion that has taken hold in certain corners of the tech world—and it is a religion—where you believe things about, for example, our "destiny" to colonize Mars in the near future, that are clearly in conflict with the basic laws of physical reality and our resources. So you have this kind of quasi-religious futurology that a certain subset of society finds very attractive, and that certain subset of society also happens to be the small subset of society that has today largely a stranglehold on the power to shape the trajectory of innovation and to decide, for example, what new kinds of companies and products will be invested in. It is all within that domain of Silicon Valley, venture capital, and start-ups that this kind of naïve vision of the future seems to have a very strong grip.

There is another factor here, though, which is that there are a lot of folks in Silicon Valley who are not in thrall to these kinds of naïve visions who actually have a pretty clear-eyed view of the world and the circumstances therein and what is needed for a truly politically and economically sustainable future. There are a lot of people in Silicon Valley who have that clear-eyed view but are nevertheless operating in a system that has been allowed to develop perverse incentives that continue to drive these harmful sorts of patterns because they in the short term reward people.

I have seen how difficult it is for people who want to take the long-term view, who want to develop technology in a way that actually will foster human flourishing in the next century, not just in the next ten years, I have seen how hard it is for them to get investment, to get buy-in, and to operate against all of the incentives that are currently running the other way—economic incentives, political incentives, media incentives.

I think we really have to treat this as not a single phenomenon but as a phenomenon that has partly a kind of cultural aspect to it and that requires a kind of cultural enlargement of different possibilities for thinking about the future than this very sterile and naïve view that drives the people who think that Bitcoin, for example, is somehow going to solve all of our problems or that going to Mars is somehow the way that we save ourselves from a planet that we continue to ruin on a daily basis.

There is that kind of naïveté, but there is also this kind of political solution that needs to be found, where we figure out how the incentives that are currently broken can be changed to reward political action that actually benefits people over the long term.

I have seen a lot of people in Silicon Valley who are terrified about the future. They're terrified for their children. You hear all these stories about folks in Silicon Valley buying up boltholes in New Zealand to hide in because they're convinced that the world is heading off of a cliff.

WENDELL WALLACH: Either that or go to Mars.

SHANNON VALLOR: Right. Yet these are the people who have the greatest power to shape our present trajectory. Even they don't believe the trajectory that they are steering us on is the one that takes us to a future of human flourishing, so the question is clearly: Why are they staying on that trajectory?

WENDELL WALLACH: Let's talk a little bit about this issue of power and ethics because, on the one hand, I think what we're saying is these perverse incentives have been creating a juggernaut that is making at least those who love those incentives and the narrative behind them richer and richer, even in the midst of a pandemic, when half of the world is suffering and billions of people are perhaps losing everything or what little they had, and this question of whether ethics can be empowered in a way in which it helps nudge the trajectory into a more positive outcome or whether ethics itself is just too weak.

You know, of course, that this debate is going on within the AI ethics circle, particularly among those of us who have championed AI ethics for years now and suddenly are bewildered by what, on one hand, seems to be our success and, on the other hand, appears to be a whitewashing of ethics by corporations, a co-optation—to return to Herbert Marcuse, who you mentioned earlier—where there is this capture by the corporations of not only our educational system and the incentives within that but a reinforcement of those values that reinforce the trajectory as it is.

So it raises this question about whether the success of the AI ethics movement itself is success at all or whether it is not dealing with the power dimensions in a way in which we can effectively diffuse some of those forces that are taking us to futures that may not be worth most of us living.

SHANNON VALLOR: Yes, that's right. We have seen this critique come from folks like Kate Crawford, who has said that what we don't need is ethics, what we need is to talk about power. In a way what that does is that gives away the meaning of ethics and it grants it to those who have cynically stripped it of any ability to serve as a critique of the unjust exercise of power.

If you say that ethics has nothing to do with power, you're giving away the game, you're giving the notion of ethics over to those who have depoliticized it, when ethics going back to Plato is fundamentally a question of justice and very much about power. Even in the Western philosophical tradition, the concepts of ethics and power and the discourse about what power is good and legitimate are never separated, even in the classical philosophical tradition, so we shouldn't indulge or permit that separation.

At the same time, it's true that the kinds of ethics that we are dealing with today do not have the right language or conceptual frames to deal with the challenges of power today, and the mechanisms that we have for legitimizing power, as we have said, are largely captured by corporate interests in ways that disable the checks and balances in the political system that were designed to constrain the unjust use of power.

So, on the one hand, I think the critique is right: The notions of ethics that we are dealing with need to be reinvested with a political vision of what it means to use power legitimately. On the other hand, what I don't want to see is a world where we imagine that by shutting ethics out and talking about power that we get anywhere at all other than the equivalent of "might makes right." If you can't talk about ethics, if ethics is of no use to you, then there is no distinction between legitimate power and illegitimate power, there is no distinction between justice and injustice without ethics, there is no distinction between power that should be resisted and power that should be sought and welcomed. There is no good politics without ethics; there is just whoever the strongest voice is in the room, who has the most guns, or whatever it is, that can do the most damage.

Again then we go back to Plato. The whole debate in Republic begins with this conversation between Socrates and Thrasymachus about whether power is just what the leaders say is good or whether it has this deeper, more robust meaning. So I think we do need to reclaim the notion of power, but I think we need to do that within the mode of ethical thinking.

WENDELL WALLACH: Of course the leaders of the tech industry will consistently argue that the only function of ethics is to restrain innovation and to restrain development, and of course that we need development for defense against now the Chinese if not the Russians again or whoever is there, but we need innovation for productivity, we need innovation to solve climate change, to cure cancer, and so forth.

I think all of that is true, but it seems somehow we have to bring a twist into the conversation of ethics so it just doesn't seem to be a bunch of constraints. That's one of the concerns I have around what have become the AI "principles." As much as I applaud what are the prevailing principles of AI, I think principles are not enough. We need to actually make the conversation about something very different.

In my thought the difference is this question of how we make decisions at all or who is the decision-maker, who does a decision-maker need to be, to make effective decisions in this context of uncertainty that has been created by the convergence of climate change and the destabilizing impacts of emerging technologies. I think if we could move the discussion of ethics away from principles and values as the lead item to the challenge of making effective decisions that don't unravel in our face or don't precipitate more problems than they solve, that would be helpful.

Some of the people who have been listening to recent podcasts that I have been on here for the Carnegie Council know that I talk about ethical decisions a lot as not being about binary choices but really being about navigating uncertainty through consideration of the real tradeoffs that are entailed in the various courses of action we take and that the languages of ethics are less about constraining decisions and more about bringing to light various elements that you would like to have factored into good choices and actions.

Furthermore, once we make a choice—and we often have to make a choice, and every choice has its tradeoffs—we should also be addressing the harms, the risks that might have been addressed more directly if we had made a different choice. We need to be engaged simultaneously in pushing forward our program, those goals, or those ends that we seek, but we have to simultaneously be ameliorating the harms that are entailed in those goals. Otherwise, we actually in the end get nowhere; we create as much problem in our wake as any supposed solution might be creating.

SHANNON VALLOR: I agree with most of that. I absolutely agree, certainly as a virtue ethicist, that a significant function of ethics is to allow good decision making under conditions of uncertainty and novelty. That's what practical wisdom is, what Aristotle called phronesis. It's the ability to act well in a circumstance where you don't have a map or a rulebook that was written for the situation.

But I think we can't only talk about navigating uncertainty or making certain tradeoffs because we absolutely still have to think about what are the ultimate values that our tradeoffs will favor and for whom and, as you say, who gets to choose what those tradeoffs will be. You could have a very vicious person who is actually very good at making decisions under uncertainty and very good at analyzing tradeoffs; it's just that all the decisions they make end up being self-serving or harmful to others.

WENDELL WALLACH: That means they're just not doing the second part of the equation I put forward, which is that in making a choice, a good ethical choice also has to include the amelioration of the tradeoffs or harms that are left in its wake.

SHANNON VALLOR: But here's what I think is missing from that. If we only talk about ameliorating harms, then what we are doing is taking for granted our existing conception of the good and the world that we would like to exist, and all we are trying to do is sort of maintain the status quo by suppressing harms that might come out and threaten it. What we're not doing in that circumstance is saying not just what are the harms, but what is the moral vision that we have and how could that moral vision be improved or enlarged?

I think we are really missing that piece in the ethics conversation right now. That is, in part, I think what is missing from the AI principles that you mentioned, which are largely focused on harm mitigation. There are many scholars who have said this better than I have—for example, Ruha Benjamin's work in her book Race After Technology is obviously more worth your time than listening to me talk about this—but this notion of the kind of futures that the current power structure has allowed to be entertained and the way those futures and those goods have been constrained by the current technosocial culture is really as important as identifying and mitigating the harms that threaten our present understanding of the world.

WENDELL WALLACH: I am going to change the subject a little bit, though it's clear that we have just scratched the surface of a topic that could be developed in a much fuller way, but I want to touch on two other topics before we close here.

One is the public square and whether present media platforms are offering us an adequate public square or could be restructured to give us an adequate public square. What I mean by "public square" is a place where we can all come together and debate out the futures we want and the values that we want to promote.

I know you have written and talked about this in the past. Perhaps you can share a few of your thoughts on this.

SHANNON VALLOR: This is something that I have spent quite a bit of time thinking about.

One of the things I have thought about is I mentioned the need to talk about ethics in light of the need for collective deliberation and decision-making, and I think one of the primary functions of the public sphere is to enable that. If you go back to Habermas, Rawls, or anyone else in political theory who talks about the public sphere, it's linked with this notion of deliberative democracy, of a sharing of power in an important way that provides the moral foundation for a good politics.

One of the things that I notice when I see the way that new technologies are shaping the public sphere is how little they do in many cases to cultivate and sustain the deliberative virtues, the ability to come together with others and listen and deliberate—and deliberation is not debate.

What you have on Twitter right now is a very vital public political debate going on every second of every hour of every day, stretching across the globe. A naïve person looks at that and says: "Hey, the public sphere is more vibrant than it has ever been and healthier than it has ever been. Look. It's accessible to anybody with a smartphone."

That was never true. It's available to people who weren't allowed to leave their homes previously and now they can participate from anywhere in the political conversation. It's very easy to look at that and ask: "All right, what's the problem? The public sphere has expanded and the modes of expression that we can add to it have only multiplied." This is all true, and those are all in many ways good things.

But what hasn't happened is any process of cultivating the virtues of public deliberation and discourse that serve the public good. We go online, we throw out our opinions, we attack other people's opinions, and then we move on. Of course, there are little pockets where you can actually see deliberative work going on, but they are not supported by the affordances of the platform design, and so they don't take hold and grow and sustain themselves.

So you have people mistaking politics for political debate and performance. A true deliberative politics is really missing in the public sphere right now, so I am very interested in thinking about how we build back the conditions that promote a deliberative exercise of power and collective decision making.

WENDELL WALLACH: It seems to me it's not just deliberative. It's relearning that we need to find ways of working together, of cooperating, of working through these issues that we all share and are going to affect not only our lives but the lives of our children.

SHANNON VALLOR: That's exactly right.

WENDELL WALLACH: Opinions are not going to solve the challenge of climate change. We need many voices at the table, and not just to be inclusive, because there are many different perspectives which impinge upon the kinds of decisions—or at least appropriate and effective decisions—we can make. As I have often said, intelligence doesn't belong to either an individual or a machine. It is collective. It is embodied culture. None of us can know everything, and we are now dealing with challenges that really require many cooperative voices and many kinds of expertise at the table together. And, yes, maybe even some of those voices in the present or future will be AIs, but, at least in the present, they are going to speak largely through the experts who know how to read their output and what their output does and doesn't mean.

SHANNON VALLOR: I would just want to pick up on what you have said about the importance of understanding that it isn't just about inclusion or even participation, if we still understand that as the model of individual preferences being entered into a ledger and aggregated. Unfortunately, that is the notion of democracy that many of us have, this notion that it is about aggregating individual preferences, as opposed to coming together and confronting shared challenges, shared opportunities, and, as you say, cooperating and working together to do things that none of us could do simply by having our own individual preferences indulged. We can have a better world through this kind of social cooperation and solidarity than any of us could have if our own individual privileges and preferences were to be indulged at every turn.

You look in fact at some of the interesting pop culture that is driving the conversation today, and I think about something like a show called Succession, which isn't about technology at all, but it's about a sort of broken family that can't escape the idea that what they're supposed to do in life is pursue their own advantage at all times, and the way that leaves them ever more broken, unhappy, bored, lost, and desperate. There is no one in that show who isn't miserable most of the time, and yet they have wealth and power that most people will never even approach.

I think it's a great testament to the sterility and sadness of a life in which we cannot see the reality of the common good or shared interests as compelling. That is part of the cultural transformation that we need in order to get to the place you're describing.

WENDELL WALLACH: This is one of the real attractions, I think, of virtue ethics and the building of character. Increasingly people—and Succession is a good example—are recognizing that they are caught in value systems, mechanisms, and power structures which actually don't really give them any choice, and they are functioning as juggernauts and they're taking them toward futures that are not viable, that are not sustainable.

Ethics and the development of personal character and so forth are actually one of the few outlets or escape valves we have, if you see that and you see that you are now imprisoned by mechanisms—some technological, some economic, some caught up in the language of security and defense—that are just not viable. They are not viable given the destabilizing challenges we have that are creating insecurity today.

SHANNON VALLOR: What you have just said is so important because even in virtue ethics, which focuses on individual character, the notion of individual character that someone like Aristotle was working with was something that was derived from an understanding of shared flourishing.

For Aristotle the highest good is eudemonia or "a good life," "living well," but the way that he understood it was "living well with others in community," and he worked backward from that to envision the kinds of personal traits that people would need to have in order for that to be possible for them.

But the ultimate good was never about simply individual virtue. The ultimate good is what that enables, which is this shared life together that is good, and that is what we have to come back to, and that is what we need to use technology to help us enable.

WENDELL WALLACH: There is one shared project that you and I worked on together, and that was a paper where we placed a challenge in front of the AI researchers who were expressing great concern that perhaps they were creating future AI systems that posed an existential risk to humanity, and their hope was that they could come up with some means of ensuring that those systems would have values that would be sensitive to human concerns. In the early days, that was referred to as "value alignment," when the value alignment terms got challenged, they changed them, and they will change them again.

But you and I were persistent in arguing with them that the models they were using for ensuring the safety of these future systems were really bereft, they really were inadequate both from an ethical viewpoint but also whether they could actually be expected to work, let alone they were all based on presumptions that these machines would have characters and abilities that we had no idea whether those could be implemented in artificial intelligence either.

We produced a paper together that was a critique of this value-alignment approach, and we basically said: "You are not going to get trustworthy superintelligence unless you can have superintelligence that really inculcates the virtues, that you really have virtuous entities; and it's not clear that we know how to create virtuous entities in humans let alone do we even understand all the characteristics in machines."

I wonder whether anything about that argument on our part has changed for you and whether you ultimately think that argument really is an argument to the technologists who are creating AI and artificial general intelligence, and perhaps artificial superintelligence, or is it more about having a discussion about what really trustworthiness means in an agent, whether human or machine?

SHANNON VALLOR: I think much of what we said in that article for me still holds true, and I think it is perhaps something that is less likely to be relevant for the development of future AI systems, precisely because the current minds of AI research are heading in directions that are so far from where they would need to be oriented if we were actually trying to build virtuous machines.

We are going in the opposite direction. We are not building machines that, for example, have more powerful abilities to gain a semantic representation of the world and how things are related to one another and why they matter, or why, for example, things that are morally significant for us should be attended to. We are not building machines to gain those kinds of capacities that are critical to the development of virtue, capacities of moral perception, and the ability to pay attention to things that are morally salient, the ability to have a relational understanding both of the relationships between humans and the relationships between humans and things. We are just not moving in that direction in AI development.

So I don't know if our critique is really that meaningful for contemporary AI research, but I think, as you say, it does remind us of what we really mean when we talk about someone who is trustworthy.

When we talk about someone who is trustworthy what we mean is we have placed something that matters in their care and we believe that they recognize the value of that thing that has been put in their care and they intend and are capable of caring for it on our behalf. That's what trust is. It's when I put something that matters in your hands and I know that you understand why it matters and what that requires you to do to care for it in the way that I would want.

We know that is not anywhere near the kind of capability that we're building in AI systems, so what we need to do is build human contexts that can embed machines in ways that allow humans to care for one another's lives, bodies, minds, and knowledge, and to care for the world in ways that trustworthy members of the human family would, and we need to have the machines that are simply aiding our ability to be trustworthy and to treat one another and one another's concerns with the kind of moral attention that they deserve.

WENDELL WALLACH: Thank you ever so much, Shannon.

I'm going to bring this conversation to a close, but hopefully the dialogue, the reflection, that we have tried to stimulate through this talk together will have at least brought some of you into this discussion about how we should be rethinking ethics if we want to make it viable and robust for the Information Age.

Again, thank you all for joining us.

SHANNON VALLOR: Thank you, Wendell.